Products vs Protocols: What Signal got right

There is a significant difference between developing and promoting a protocol (such as XMPP) and a product (such as Signal). Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. This post details how and why Snikket aims to strike a balance between the two.

Products vs Protocols

This past weekend I gave a talk at the (virtual) FOSDEM conference about a topic I’ve been thinking about a lot the past few years - the differences between developing a product and developing a protocol.

You can watch the talk here, but there were many things I wanted to touch upon that wouldn’t fit into the 20 minute slot. This post will cover the same topics, but expands on some of the points I discussed.

Previously, in open protocols…

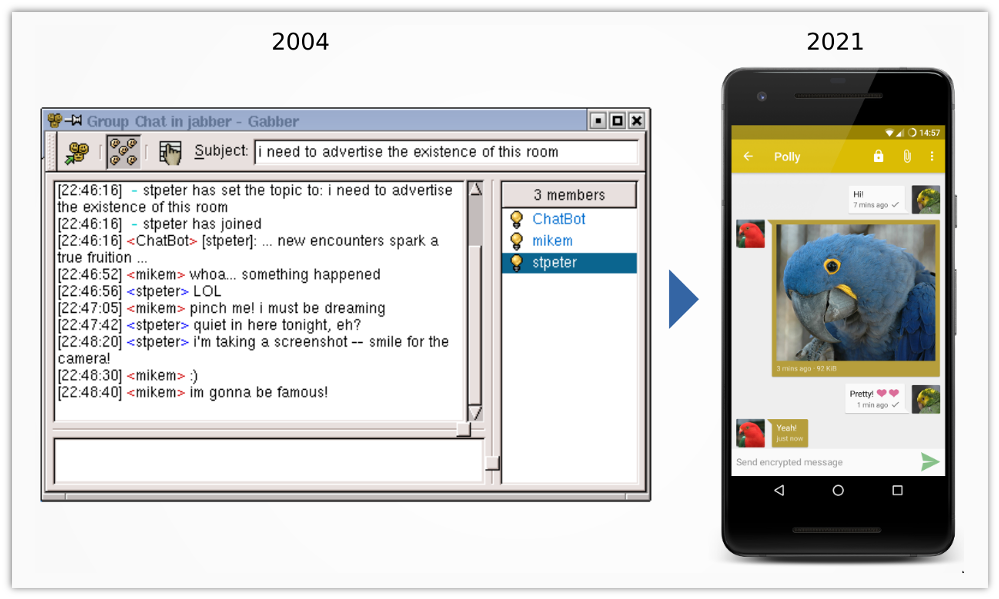

I’ve been involved with XMPP (once known as Jabber) for over 15 years. It is now over 20 years since XMPP’s inception, and over this time XMPP, along with the rest of the tech industry, has seen significant change.

XMPP began life in the late 1990s, as an attempt to break into the messaging silos of that era. The names and logos may have been different, but it was a very similar landscape to today - oversized tech companies fighting each other for control over people who simply want to use the internet for what it was designed, communicating with one another.

Email got lucky. A standard protocol managed to break down the walls of even the final fortress of resistance, AOL. This was achieved largely because the adoption of standard protocols by smaller providers allowed them to form a network together that began to threaten even America’s largest ISP.

Unfortunately we never quite reached that point with instant messaging. However that hasn’t stopped many of us from continuing to strive for a similar outcome even as our symbol of hope, the open email network, is under threat today more than ever before.

Despite numerous projects, communities and organizations campaigning for decades in favour of open messaging systems, the space is still dominated by large silos. The largest the world has ever known. WhatsApp alone has over 2 billion users. That means a significant portion of the world’s communications are flowing through a single company. A company that has a simple business model - amassing data about people and leveraging that data to help their actual customers (other businesses) influence the beliefs, biases and behaviour of the users of their platforms.

The slippery slope

Despite the dizzying numbers associated with WhatsApp today, it had more humble beginnings. Founded by two ex-Yahoo employees, Brian Acton and Jan Koum, it began as a simple messaging app for iPhones. The server was originally based on an open-source XMPP server, and used the XMPP protocol. However the goal of WhatsApp was not openness and federation, and they soon diverged far from standard XMPP.

As WhatsApp grew, early users may recall that they also began charging a small fee for accounts ($1/year). Their reasoning was simple:

“Remember, when advertising is involved you the user are the product.

Your data isn't even in the picture. We are simply not interested in any of it.

When people ask us why we charge for WhatsApp, we say ‘Have you considered the alternative?’“

Nevertheless, just two years later it was announced that WhatsApp had been acquired by the internet’s fastest-growing advertising platform, Facebook.

Despite declaring to the EU competition commission that linking an individual’s data between WhatsApp and Facebook was not technically feasible this is exactly what they went on to do, leading to a €94 million fine. Little by little, Facebook has been loosening their privacy policies to allow them to absorb WhatsApp data into their daily operations.

So when, in early 2021, the latest update to the privacy policy gave users of the platform a clear ultimatum to allow this sharing or close their account, many users wisely began to seek alternatives. Finally, the moment we had been waiting for had arrived.

Many of us advocates of open communications seized the opportunity, and recommendations were soon flying around for the wide range of alternative messaging systems we’ve been building these past years. “Use XMPP!”, “Use Matrix!”, “Use Signal!”, to name a few.

Despite a marked increase of signups on XMPP and Matrix servers, of these three it was Signal that won by far the largest share of new users. Millions of people flocked from WhatsApp and overloaded Signal’s servers, resulting in disrupted message delivery across Signal’s service for days.

This service disruption was possible because, unlike XMPP and Matrix, Signal is centralized, and all messages flow through a single set of servers, the same model as WhatsApp.

XMPP and Matrix are both federated networks. Rather than a single entity controlling the network, there are many servers to choose from, run by many different independent providers. Even with a server down, overloaded or closed to new users, the rest of the network continues functioning.

So why did Signal receive millions of users, and XMPP/Matrix did not?

Signal

At this point it’s impossible not to reference The Ecosystem is Moving, a 2016 blog post by Signal’s founder and CEO, Moxie Marlinspike. In this post Moxie details all the problems he sees with protocols becoming open internet standards. In particular, that they lose their ability to evolve, and that evolution is vital to compete in our industry’s “moving ecosystem”.

We got to HTTP version 1.1 in 1997, and have been stuck there until now. Likewise, SMTP, IRC, DNS, XMPP, are all similarly frozen in time circa the late 1990s.

Well. Far from being frozen in time, XMPP has changed significantly in the past 20 years.

Just some of the things we have now that we didn’t have in the beginning:

- End-to-end encryption using OMEMO (based on Signal’s protocol and audited), with multi-device and offline capabilities

- Audio/video calling (now 2nd generation, encrypted, WebRTC-compatible)

- Mobile optimizations (bandwidth, connectivity, push notifications)

- Full cross-device message synchronization

Many of these things didn’t even exist as concepts back when XMPP began. Adding them was only possible due to XMPP’s smart design: a core protocol, with a suite of extensions (known as XEPs). New extensions are added as needed, and irrelevant ones get deprecated.

To help keep everyone on the same page as the protocol evolves, the XMPP Standards Foundation (XSF) annually publishes the recommended XEPs that different classes of software (e.g. instant messaging, social networking, or smart devices) should be implementing. These round-ups are known as compliance suites.

The documentation site Modern XMPP also serves as a useful reference guide for modern XMPP implementations (including UI/UX considerations, which are not covered by the protocol-level documentation).

The unfortunate truth

The effort required in advancing the protocol is significant. And that’s not even counting the implementation work. XMPP has a diverse and open ecosystem. There is no single “XMPP client”, instead the ecosystem is composed of… just about anyone who decides to write XMPP software. The vast majority of this software is free/open-source, and developed by volunteers and communities.

Publishing protocol updates does not magically mean the changes are implemented in all XMPP software overnight. Some projects are more active than others, and each contributor is an individual with their own life and work schedule. Unfortunately this means that it’s very difficult to evolve the protocol and keep everyone 100% in sync. Luckily XMPP’s modular design makes it easy for some software to advance ahead of others without having to lose backwards compatibility with the rest of the network. If we didn’t have this feature, we would always be in a state where half of the network is unable to communicate with the other half of the network, or more likely we would be stuck with the initial set of features because nobody would want to be the first ones to become incompatible with everyone else.

But Moxie is right. We could move much faster if we didn’t care about interoperability, software diversity, and decentralization.

And that is the approach Signal is taking.

Product or protocol?

It’s clear that there are trade-offs to be made here. Signal’s product-led development excludes others from participating in the Signal network. But it allows them to remain agile, and implement new features as fast as they can write and ship code.

I put together some of the trade-offs into the following table:

| Building an ecosystem | Building a product |

|---|---|

| Focus on protocol | Focus on implementation |

| Mostly documentation | Mostly code |

| Cross-project collaboration | Single project/team |

| Building for developers | Building for end-users |

| Slow evolution | Evolves as fast as you want |

| Achieve diversity | Achieve a monoculture |

| Robust | Single point of failure |

I think that Signal’s approach is laudable for the number of people that they have helped divert from data-mining platforms, and helping to remind people that surveillance capitalism isn’t the only way to do things.

They’ve built a good user-friendly product, and they have done it with security and privacy at its heart.

But we have to aspire to more than this. Signal is a centralized, closed system. That means to communicate with your contacts who use Signal, you must also consent to their terms, their software, their US jurisdiction. You have to be okay with their servers being hosted with large cloud providers such as Amazon and Google.

But one thing the past has shown us is that things change. Technologies evolve, business leaders come and go, motives adjust. Signal today may be as benign as WhatsApp before its acquisition by Facebook. But change is inevitable, from whatever direction it comes. Signal is a technical, organizational and political point of failure.

Best of both worlds

Thinking about the table I presented above. Consider that perhaps the options on each row are just the extreme positions. Perhaps we can try to strike a balance between them - making intelligent choices as we go.

What if we could make a Signal that was a little more open? And an XMPP that was a little bit less diverse? Accept that we would trade some of the agility for robustness, and some of our diversity in favour of consistent usability.

Can we move beyond Signal’s flaws to build something that is open, interoperable, user-friendly, consistent and decentralized? I believe so, and as they say, there’s only one way to find out.

Snikket

Snikket is an initiative to bring a more product-led approach to the XMPP ecosystem. It’s a project that will deliver a suite of XMPP software: a single app for each platform, and an easy to deploy server for self-hosting.

The goal is to reduce fragmentation in the XMPP ecosystem, and ensure that people have access to a familiar brand across all platforms. This brand will represent a consistent set of features, and no interoperability issues. The software is all open-source, and of course still (the latest and greatest) XMPP.

Hopefully Snikket will also become an easy gateway to the world of XMPP for users who may previously have found it inaccessible due to the need to understand the ecosystem and choose the best software for each platform. All the other XMPP software continues to exist, and people are free to use anything that better suits their needs.

Starting from scratch would be a massive undertaking, and would require resources beyond the reach of an unfunded open-source project. Instead we are building on top of the amazing work that is already being done in XMPP implementations. For our Android client we selected Conversations. For iOS, Siskin. The server is based on Prosody.

All of these projects are good projects on their own. But by combining them under a single brand, performing focused interoperability testing and improving UI/UX consistency, we gain a new project that is greater than the sum of its components.

To be clear, these are not “hard forks” of the projects. Quite the opposite. We work closely with the developers, and have sponsored features in both Conversations and Siskin to get to where we are today. Our work on invite-based onboarding grew into a whole new feature in Prosody. Everything that makes sense in the upstream project gets pushed upstream. Lessons learned in UI/UX will likewise get added to the Modern XMPP documentation for other client developers to benefit from.

Snikket is not about replacing any of the individual projects, but about joining them together in a neat way and extending XMPP’s reach to new audiences.

Back to the future

Will Snikket alone turn the tide against proprietary communication platforms? Maybe, maybe not. But we’re part of a growing movement that agrees it’s time to stop repeating history, and finally redecentralize the internet, the way it was intended.

Thanks to Kim Alvefur, Georg Lukas and Jonas Schäfer for their editorial review during the writing of this post.

Want to help support the project? Donations are welcome! All contributions will help us to continue work on the project and accomplish the goals on our roadmap. Want to talk? Join our community chat.

Snikket Blog

Feed

Subscribe to our RSS feed for the latest updates from the Snikket project!

Recent Posts

- Snikket at FOSDEM 2026

- A new look for Snikket Android

- Snikket Server - December 2025 release

- Introducing Borogove, the new Snikket SDK

- Snikket Server - November 2025 release

- Snikket Server - September 2024 release

- Snikket Server - July 2024 release

- Snikket Android app temporarily unavailable in Google Play store [RESOLVED]